While the national debate over homework continues, a teacher in Wisconsin finds that his students learn better without it.

Regardless of where you stand on the issue, there's no doubt that the anti-homework movement has been picking up steam. Homework is still a staple in most classrooms, but even teachers who believe it has some value are scaling back. Others, convinced homework is a waste of time and even counterproductive, are phasing it out — a decision that is becoming less and less controversial with parents, school leaders, and researchers.

The scrutiny stems not only from homework's questionable academic value, but also its role as a stressor in students' lives. In particular, the practice of assigning homework to elementary students has been widely criticized.

While most researchers agree that homework in elementary grades has no benefit, many believe it can be useful, in moderation, in high school, particularly in preparing students for college workloads.

But some high school educators are taking a second look. Christopher Bronke, an English teacher at North High School just outside of Chicago recently scrapped homework in his 9th grade class. To Bronke, it “just made sense.”

“I got sick of a wide range of factors: overly stressed students, poor-quality homework,” he explains. “They didn't have time for it, and very little actual learning was happening. I made a very simple decision: I would rather get through less material at a higher quality with less stress than keep giving homework.

“The results have been great. My kids are happy, healthy, and learning!”

Scott Anderson, a math teacher in Juda, Wisconsin, believes a teacher doesn't necessarily have to be “anti-homework” to take the class in a new direction.

“In certain circumstances, I guess homework can be good,” says Anderson. “But I prefer to skip good and do great.”

Anderson came into teaching as a second career in 2006. In his first couple of years in the classroom, he was a self-described “strict traditionalist.” Anderson assigned homework — up to 30 Geometry and Algebra problems a night - because. well, that's what teachers did.

“That was me, standing in front of the class, lecturing, handing out homework. That's how I was trained,” he says.

But gradually Anderson became convinced that something was wrong. Too many graduating seniors weren't ready for college-level math.

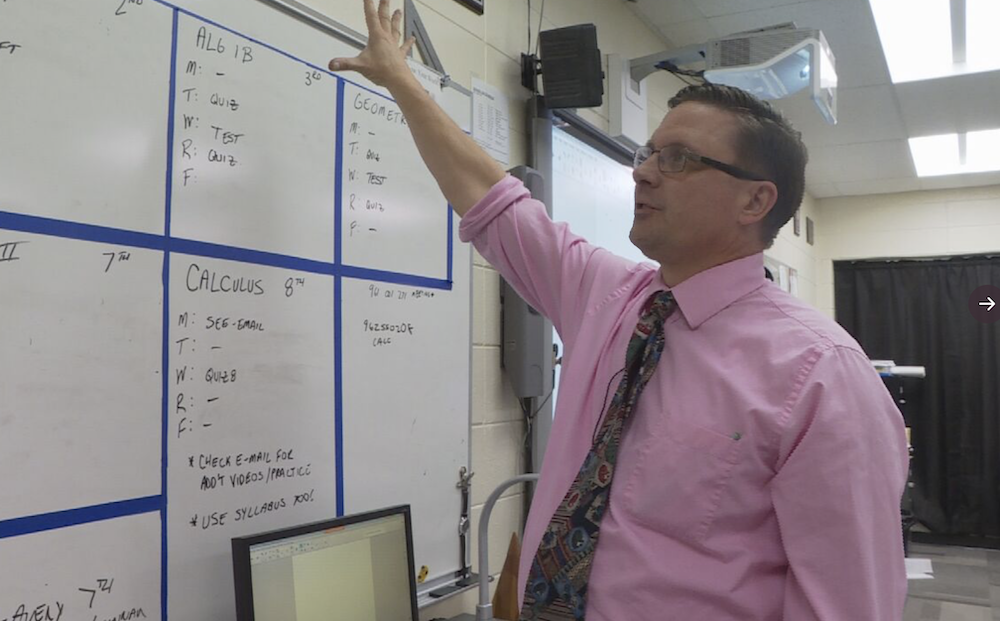

Scott Anderson (Photo: Channel 3000)

“It wasn't working. The kids weren't learning; they were doing the problems wrong. Something had to change.”

Another concern was the “homework gap.” Juda is a small, rural school district (student population: 310) and some students don't have adequate access to the Internet, impairing their ability to wade through too much homework. Believing all students have this access, says Anderson, is a “gigantic assumption.”

Anderson gradually scaled back the amount of homework. He started out by reducing the number of math problems from 30 to around 12 and continued from there. By 2016, homework went from 25 percent of a student's grade to only 1 percent.

As he proceeded, Anderson looked through the existing research on homework. He understood that assigning some can have benefits, but he concluded that homework was not adding enough value to justify the time students — and Anderson — put into it.

A no-homework policy was just the beginning. “I took a butcher knife to the curriculum. I thinned it something fierce,” he said.

With homework becoming more scarce, more time was freed up in the classroom for practice. No time in Anderson's class is wasted. “Even before the second bell rings, we're working the problems," he says. "I try not to lecture much more than 8-10 minutes each class.”

Because homework used to be such a large part of the grade, Anderson contacted parents to inform them of the changes in policy. Initially, there was a bit of grumbling because the number of A’s in his classes declined about 20 percent. All of a sudden, doing well in his class was based on what students had learned, not how many assignments they had cranked out.

In certain circumstances, I guess homework can be good. But I prefer to skip good and do great.” - Scott Anderson, Juda High School

Grades in Anderson's class are now based on tests and quizzes. If students struggle, Anderson allows them to take them as often as needed to master the material.

According to standardized test scores, the results of the no-homework policy have been positive.

“We have been able to document the improvement of our student body moving roughly from 30 percent not ready for college math to almost 100 percent being ready,” Anderson said.

Anderson acknowledges that teaching in a small district grants him significantly more flexibility in phasing out homework (let alone taking a “hatchet to the curriculum”) than many other educators may be used to. Anderson isn't just a member of the Juda High Math department; he is the math department. The school's principal, Judi Davis, is also the district superintendent, and a supporter of Anderson's new policies.

Less red-tape aside, Anderson believes that his approach can work in larger classrooms in larger districts. He gives a presentation at math conferences around the country called “Minutes Matter: Moving Away From Daily Homework.” The reaction is generally positive, although the skepticism can be palpable. The main concern centers around a belief — supported by some researchers — that without homework at the high school level, students go onto college underprepared for the rigor that awaits them.

“Our job in high school is to guarantee that students pick up these skills. That's my mandate, which is different from a college professor's in my opinion,” says Anderson. “I believe strongly that my students are much better at math now than they were a decade ago.”